Week 4 Webinar Report: Food for Thought- Towards an environmentally sustainable and socially just food system

Date: 13 April 2021

Week 4 of “Bengaluru’s Climate Action Plan: Making it Participatory and Inclusive”

Recording

Background

Earlier this year, Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) voluntarily committed that the metropolis of Bengaluru would take steps to achieve the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement: i.e., to take local action that would help the world contain global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels.

On the occasion of World Water Day, Environment Support Group (ESG) commenced a webinar series to discuss and debate what it takes for Bengaluru to become a climate friendly metropolis. The webinar series is a process of engaging with multiple thematic issues, concerns and imaginaries with leading officials of various State and civic agencies, subject matter experts, youth, representatives of various sectors and residents from diverse sections of the city. And it is also a process of collectivising diverse views and solutions with necessary nuance.

In coming together this way, the steps necessary for effective and just waste management, provisioning adequate water and safe housing for all, ensuring universal public health and public mobility, providing infrastructure that is inclusive, and building energy systems that are earth friendly, along with governance that is decentralised and deeply democratic will be interrogated and pragmatic solutions identified for action. In the process we hope to construct an assemblage of visions of Namma Bengaluru and how the metropolis can survive with its limited resources for the benefit of present and future generations and the good of the world.

Week 4: Food for Thought- Towards an environmentally sustainable and socially just food system

Mr. Ayush Joshi, Research Associate at ESG, set the tone for the discussion drawing attention to the impacts of carbon intensive processes embedded in cultivating food and transporting it to faraway consumption centres. He highlighted the paradoxical nature of food production and supply that a country which is a principal exporter of rice to the world is also home to a girl who died begging for rice – a clear indicator of the persistence of structural injustices and wide prevalence of systemic inefficiencies. Enquiring how food systems are just looked at from a macro perspective, he asked:

“What it required to feed affordable and nutritious food to the city daily. What do we understand when we say Bengaluru has signed up to the Paris agreement? Are we going to grow our own food? Will there be restrictions on food coming from several 1000 miles? Will there be more terrace gardens and community gardens? Will there be more opportunity for the poor to find a livelihood?”

Prof. Prakash Kammardi who was Chairman of Karnataka Agricultural Price Commission highlighted that besides staple cereals and pulses, fruits, vegetables and dairy products are major foods consumed. Supplying dairy products has largely been achieved by the Cooperative system. But a similar strategy has not been fully adopted to the supply of fruits and vegetables. And herein lies the opportunity to support the future food needs of a massive metropolis like Bengaluru.

Prof. Kammardi offered an analysis of the quantity of different fruits and vegetables being supplied to Bangalore city from seven neighbouring districts noting that the per capita supply of fruits per day was 366 grams, well above the ICMR recommendation of 300 grams. Similarly, the supply of vegetables per capita daily amounts to 441 grams, again well above the daily dietary requirements prescribed nationwide. From all of this data he concluded that Bangalore does not face issues of shortages in the supply of these essential commodities. However, an important factor is that these figures are just averages, and with prevailing socio-economic disparities it is highly likely that people from lower income groups within the city do not receive adequate nutrition.

Prof. Kammardi also explained how major players in the supply chain: the farmers, the vendors and the consumers, need to be organised so the process continues sustainably, and without being monopolised by profiteering transnational corporations. He noted that as the farmer expends all her efforts in growing food, she is unable to focus on selling this food to consumers. Thus a supply chain is necessary. This is where the vendors come in. He estimated that there are between 3 – 5 lakh vendors and hawkers who supply fruits and vegetables to Bangaloreans and they could easily become the basis for a sustainable food system to support the metropolis’ food needs.

He also highlighted that the existing model of supply chain – nobody really gets a good deal – not the farmers, nor the vendors, not even the consumers. He felt that there was an urgent need to make the entire system just and equitable. In order to do this, he advocated the implementation of a Cooperative model, similar to the model followed in the supply of dairy. He also felt intelligent and compassionate use of digital technology would help a great deal in the creation of this model.

Prof. Kammardia cited the example of Malur to throw further light on what such a system could entail:

“Malur Town is a major supplier of vegetables to Bangalore. The Farmer’s group in Mallur can have connections with the vegetable vendors association in Bangalore to have a cooperative platform. Creating such a cooperative, digital supply chain platform will help to seamlessly link consumers to producers.”

Another important aspect that Dr. Prakash touched upon was the high degree of toxicity in much of the food consumed now. Studies reveal that cabbage farmers around Bangalore use 147% more pesticides than is recommended as per University of Agricultural Sciences norms. Several labs have noted that cabbage, along with many other fruits and vegetables, are highly contaminated. He noted that much of the milk and dairy products we consume are also contaminated, containing several pesticides which are banned.

Concerned about the toxicity in food grown with chemical inputs, Prof. Kammardi said that the receptivity of Bangaloreans to organic produce is high. Through this survey, he found out that Bangaloreans are willing to pay a premium of 20 – 30% for organic foodstuffs. He advocated for greater education and support to farmers to help them transition away from chemical-based agriculture. The cultural dimensions of the food we eat is critical, he highlighted:

“Food is not just about filling our stomachs. There is so much tradition, so much heritage in it. We should strive to eat native varieties of different foods – the country chicken, the naati tomato, cereals like millets. These will truly take us back to our roots”

Ms. Juli Cariappa, Co-creator, Kracadawna Organic Farm felt Bengaluru is in a dire climate crisis already, which was also perceptible from the collapse of economic, social and health systems of the city after lockdowns were imposed. She drew attention to the fragile structure of cities that humans have attempted to build over many centuries through trial and error, referring it to as a complex life symbiosis. Such fragility of cities is owing to the fact that it’s a synthetic structure that has almost no natural control to restrict various parameters, unlike feedback systems that exist in natural biomes like a forest, she pointed out. The great challenge for designed structures is human want, which always exceeds what we is originally estimated, and this quickly results in commodification of resources. Such commodification causes inequitable distribution of resources and enlarges the gap between the haves’ and the have nots.

“Without each person cooperating in the care of the city commons, resilient food systems cannot be created.”

She expressed how humans have a tendency to be driven by individual aspirations, overlooking the culture of a civic responsibility. Lifestyle choices tend to have very serious and detrimental effects on aggravating crises such as climate change. She pitched the example of a supermarket to explain the human instinct of satisfying all wants at one stop. She argued that such choice of convenience often neglects the associated environmental cost such as the greenhouse gas emitted from automobiles while travelling to the supermarket. The conversion of fertile hectares of land into hypermarkets and malls defeats the purpose of sustainability as we lose out on areas that also supported watersheds and living biomes.

“Actions speak louder than words. People will see that spaces can become neighborhoods and those in turn can become places for a food commons. At least a part of a neighborhood’s needs can be met with friends and families working together to reclaim the city, finding sustainability and self- reliance at their doorstep.”

Vegetable beds at Kracadawna, the farm Juli stewards in Nugu River Valley

The chemicals and pesticides required to grow industrial foods that end up on the shelves of supermarkets is often grown on poisoned water and saline soils, the run-off of which comes back to the city of Bengaluru from the Cauvery watershed. She said that this process has now put the ‘garden-city’ in a feedback loop which culminates into less life and more poison for its citizens. She contemplated the possibility of securing food that is safe for the metropolis under this scenario in a non-extractive way and remarked that such conversations can not commence unless the citizens introspect and interrogate the systems themselves.

“There is a need to take accountability for the choices one makes.”

She referred to the Rio declaration that put citizens in the driver seat to make the necessary change in practicing a climate friendly lifestyle and stressed the need for:

“Rebuilding a relationship with the city, treating it as if it were your own body, (which it is) could maybe initiate the positive impulse towards cleaner air, living water, nourishing food, healthier farmlands, flourishing parks and a happier way to live.”

Ms. Cariappa highlighted the importance of soul-searching and introspection to enact real change in lives and urged that everyone must treat the state of the world very personally to find real answers. She believes small steps can bring big changes in perceptions and instill hope and inspiration, to look beyond the self and into the wild and care for it. She also highlighted the critical importance of learning to grow one’s own food with friends, neighbours and family, and that such ways can bring sustainability and self-reliance even in complex city structures. She hoped that the day the city learns to eat purposefully, it will be able to connect to rural communities and revitalize local traditions and cultures, and acknowledge the resources one must nurture and not abuse. She concluded by saying that balancing human need with environmental health, and a safe, abundant food supply, are the elements of a city primed for positive change.

Dr. Kshitij Urs, State Head, Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network began his intervention by drawing links between climate change and the cannibalistic system of urbanisation, wherein cities, especially in the Global South, are insatiable in their appetite for growth. He went on to reveal that he recently contributed to the Government of India’s document at the COP 24 Summit. From this experience he has observed that the policy framework in India hardly talks about the governance structure that is required for cities in the era of the climate crisis. In order to deal with the exigencies of climate change, he felt that we need a form of governance which is flexible and informed by science, noting that our existing systems are far too rigid.

“If we are serious we have just 15 years to exercise our political will and ensure the Earth doesn’t become uninhabitable. Cities occupy just 2% of land on the planet but contribute over 70% of greenhouse gas emissions”.

Dr. Kshitij then went on to highlight the importance of rainfed agriculture, particularly in the context of Karnataka. He noted that Karnataka is the second driest state in India and 16 of the 24 drought prone districts of India are in Karnataka.

He pointed out that the food security of urban populations across the world is at risk due to decreasing yield of staple crops, noting that the city of Bangalore is particularly vulnerable and shows up as a red dot on this map. Even as cities grapple with issues of food security, Dr. Kshitij pointed out that they are also at the core of contributions to climate change, and advocated for greater regulation:

“Cities have to be regulated. While it’s challenging, it’s also an opportunity. Regulating a small space like a city is relatively easier than regulating the larger world. There are existing models of cities with climate-friendly regulation for us to follow”

In Dr. Kshitij’s mind, a major component of climate resilient regulation would be the institution of more sustainable agricultural practices. If agriculture was practised in a socially just and ecologically sound manner, he felt that it would contribute towards meeting 12 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. However, in its current industrialised, corporatised form, agriculture contributes to several grave ecological problems, climate change being just one of them.

As the State head of the Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network (RRAN), Dr. Kshitij has been working tirelessly to strengthen support for rainfed agriculture. He pointed out that 61% of farmers in India rely on rainfed agriculture and 55% of the gross cropped area in the country is primarily rainfed. Despite the serious lack of public investment, rainfed agriculture makes a substantial contribution to food security in the country – providing 40% of rice, 69% of oilseeds, 88% of pulses and 89% of millets grown in India. However, he noted, that most farmers practising rainfed agriculture are still reliant on chemical inputs.

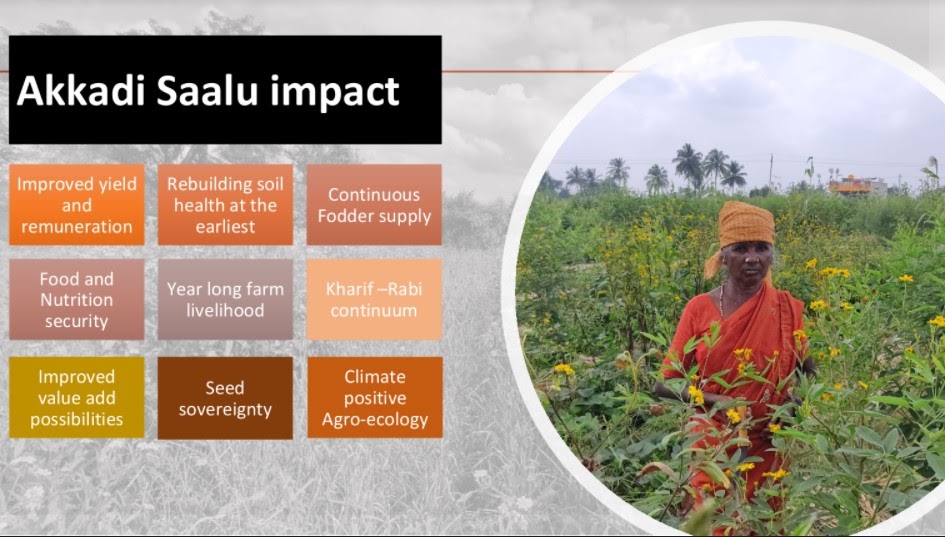

As an alternative to this, Dr. Kshitij advocated for a return to traditional sustainable practises of agriculture – such as Akkadi Saalu. Having existed in Karnataka for centuries, if not millenia, Akkadi Saalu is an agricultural practice which involves the usage of zero chemical fertilizers, zero chemical pesticides and minimal groundwater. As a part of study conducted by RRAN, several positive impacts have been observed in plots that practise Akkadi Saalu:

Dr. Kshitij concluded his intervention by highlighting that sustainable agricultural practises can play a huge role in mitigating climate change, by helping to sequester carbon in the soil. At the same time, he highlighted the prevailing agrarian distress in India and noted that shaping of market architecture in a way which guarantees better remuneration would incentivise farmers to grow sustainable, organic food. For all of this, he felt that urban consumers have a big role to play:

“It is necessary to create a demand in urban, ecologically conscious people for food that is healthier – food that doesn’t just sustain us, but also our planet. This will ensure that sustainable agriculture is profitable for farmers and also create an avenue for urban consumption to actually be climate positive, instead of contributing to climate change”.

Ms. Vishala Padmanabhan, Founder of Buffalo Back Collective commenced by narrating her experience of farming which she took up 15 years ago driven by the idea of connecting farmers directly to consumers that most organic movements have in common. She said that the past 10-12 years has taught her valuable lessons on how agencies and support organizations/institutions are crucial to any movement. She cited the example of using concepts like ‘virtuous rent’ in place of just ‘rent’ to explain how interventions from various exercises has been used to leverage this cause in both city and rural landscapes. The prime focus is always to question how to bring change and convert real agency roles into that of virtuous agencies to incorporate them into the narrative of fair trade is what she pointed out.

She further explained how there’s more sense in helping farmers organize themselves rather than just connecting them directly to the consumers to increase their efficiency in the supply chain. One of the key aspects of learning, that Ms. Vishala said has happened in the last 2-3 years in Bengaluru, is about the demand side of the whole ecosystem. Ms. Vishala highlighted ESG’s question ‘What will it take for everyone in the metropolis to return to consuming food that is healthy, locally grown and environmentally sustainable?’ which made her contemplate on how farmers can be organized to deliver the same.

She expressed that the dominant narrative for people not opting for organic food arises from lack of trust and the factor of pricing. Including consumers to be active stakeholders in the certification process is a way to build trust. With this idea, she has approached apartment complexes, resident welfare associations, communities to be part of such a process. She also debunked how the major data floated in the internet with regards to the growth of the organic sector is highly exaggerated, and that organic foods consumed today is insignificant. She drew attention to a study called ‘Hungry Cities- Bangalore’ which revealed that the small grain shops, kirana stores, meal cart vendors and hopcoms were the biggest influencers when it came to consumption in the city.

“Small grain carts, ragi mudde meal carts, hopcoms and informal vendors are the biggest influencers on urban food systems here.”

The dynamic population of the city has a huge impact on the food that is consumed, observed Ms. Vishala. She referred to the shift in preferences of food that has taken place in the metropolis due to large scale migration from the northern states of the country which in some ways is substituting the local ragi-mudde food culture which is more carbon-friendly when it comes to cultivation. She also mentioned her experiences with FSSAI to instil right food systems in place that work on decentralized communication prepared by local governments based on the understanding of local foods. The aim is to break institutional silos created by food, remarked Ms. Vishala. She highlighted the critical importance of using LPG supply chains to disseminate communication on healthy food cultures.

Ms. Vishala also advocated for multi-institutional stakeholder groups to start food policy dialogues that are conducive for cities like Bengaluru. She called for a collaboration between the Ministry of Health, ICDS, the mid-day meal system to talk and communicate about nutritious food systems, which also forms a larger part of the advocacy work that she has been involved in. She concluded by calling for active participation, getting consumers to exercise their rights to demand for good and healthy food. She attacked the notion that organic food is identified as elite food, and argued that it must be everyone’s food. She called out the lack of support to organic food systems by state departments working in urban areas and said that if the demand side for organic food catches up, real transformation in food can be seen in the metropolis.

“Consumers need to advocate for food issues as citizens and must normalise organic food as something which is not elite.”

Mr. Leo Saldanha of ESG brought in a different dimension to the conversation. He expressed the lack of text and material in BBMP’s commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement and questioned if this decision would involve consulting with the ‘right kind of public’. Reiterating Dr. Kshithij’s concept of planetary boundaries said cities also have limits and cannot function bereft of environmental limits. He also highlighted the carbon footprint involved when food is transported from one part of the world to another because of the elastic force of globalization. He opined how cities have become more extractive in nature than they were half a century ago. Owing to the dynamic nature of urban cultures, he asked if farmers too can become dynamic and how such transformations can be promoted in the years to come.

Ms. Vishala responded by saying that the future of Bangalore from the perspective of food makes her apprehensive, especially when she views the projected population for the city. She said that not only is the city growing by taking over fertile lands of the peri-urban areas, it is also simultaneously demanding more food. She raised the issue of unsustainability in existing structures to tackle such demands of food in the city, and urged focus on small enterprises is key to adapt to local food systems. She also stressed the need to integrate urban gardening to make cities food secure, and that this needs to be turned into a very meaningful movement. She reminded participants about the importance of inculcating the spirit of food citizenship to be able to embrace food security.

Dr. Kshithij said there is a misplaced conception that cities have a birth right to keep growing, which, incidentally, has been dented by the pandemic in some ways. The process of urbanization itself has to be questioned. He drew our attention to the Bengaluru 2030 Masterplan and called it a ‘horrendous document’, ‘a recipe for disaster’, when it came to environmental sustainability of Bangalore.

Ms. Juli re-iterated that re-structuring Bangalore is crucial; there is a need to think smaller rather than dream bigger and to regulate factors associated with food of a metropolis. She questioned the viability of certain plans like harvesting wild foods on the side of the road, given the toxicity involved. There is an urgent need for pro-active roles from residents of the city to engage, dialogue and believe that ‘small is beautiful’ and to limit the growth of cities. She says that we have to stop the brain-drain from the villages so that they keep growing good food and how fundamental that is to tackle climate change, unplanned growth and food security concerns.

Mr. Leo Saldanha took the discussion forward and spoke about the impact of policy interventions like the recently passed farm laws. He questioned the intent of the laws that commodified and financialized farmlands while paying little or no attention to the state of farmers or the quality of farming. He also shared the experience of Mr. Manjunath who had worked with Monsanto and realised the horrors of GM cotton and has now moved on to natural farming.

A very critical question was asked to one of our speakers, Dr. Kammardi, about incentivising small and marginal farmers to practise organic farming given the high cost of input and inaccessibility involved. Dr. Kammardi responded that organic farming is costly and gave a comparative cost analysis of 1 kg of fertilizer to that of one basket of compost. He explained how fertilizers are subsidized and that there is a need for policy reconsideration in this matter by putting farmers at the centre. He drew attention to a critical need to view organic agriculture not from the lens of conventional agriculture. He also suggested promoting farming that suits the ecology and geography of any region should be promoted to make it cost-effective, sustainable, culturally driven and farmer-friendly.

Another important question raised was on how tobacco cultivation is being promoted through FPOs. Ms. Vishala addressed the question through her lived experience of cotton cultivation in certain districts that was highly extractive in nature. She said that the entire district had transitioned to growing cotton from food crops in the last 10 years through producer organizations and largely catered to the cotton mill industry. They rely on food brought in from other parts now as they have been hooked to producing these cash crops which does a lot of damage to food crops and resources of the region. She concluded by saying that the tobacco industry might also follow the same route if promoted. Dr. Kshithij also weighed in on the question and called for a need to examine the promotion of FPOs by the governments as a panacea for rural distress.

Dr. Kammardi in his concluding remarks highlighted the immense potential of the Food Security Act to expand access to nutritious food under the public distribution system. He opined that this can serve as a wonderful opportunity to enhance the food security basket of consumers and must be thought over.

ESG will continue the webinar series “Bengaluru’s Climate Action Plan: Making it Participatory and Inclusive” next Monday, 19 April 2021 (6.00-7.30 pm on Zoom) addressing the theme: “Securing Biodiversity Rich, Healthy, Socially Inclusive and Economically Viable Commons in Bengaluru” where we explore the way forward for the metropolis to return to consuming food that is healthy, locally grown and environmentally sustainable. More details on this webinar series can be accessed at www.esgindia.org. A recording of the webinar is accessible here.

Speaker Profiles

Ms. Juli Cariappa, Co-creator, Kracadawna Organic farm

Ms. Juli has been a student of living ecology for 35 years. She is the co-creator of kracadawna organic farm in the Nugu River Valley, and a pioneer in sustainable living and healing. Since 1986 Juli along with Vivek Cariappa have sustainably stewarded their land and created a community of children, animals, plants, trees and wilderness. Countless organisms and biodynamic and organic principles of conserving the soil ecology have helped her learn the importance of linking livelihood with sustainability in everyday living.

Dr. T.N. Prakash Kammardi, Retired Professor of Agricultural Economics, University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore

Mr. Prakash has over 30 years of experience in teaching and research in the fields of agricultural, natural resources, environmental economics, traditional knowledge and indigenous technologies ect. He was a Former Chairman of Karnataka Agricultural Prices Commission, Govt. of Karnataka. He has published over 30 Research papers, more than 50 scientific papers, 25 Books and more than 100 popular articles.He has been a recipient of many prestigious awards like Agricultural Diversity Research Award from International Development Research Center, Canada (2001), First Scouter Award received from Dr. Abdul J Kalam, Honorable ex-president of India in promoting unaided, grassroots green technologies given by National Innovation Foundation, Ministry of Science Technology, Govt. of India (2002).

Mr. Kshithj Urs, State Head, Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network

Mr. Kshithj Kshithij Urs is deeply committed to social justice and a healthy planet. Kshithj is also an organic farmer. He has worked at the intersection between academics, activism and policy advocacy for over 25 years. He has a medical graduation from Bangalore, a Masters in Science in Development Studies from SOAS, London and a Ph.D from the National Law school of India University enquiring into the impact of water sector reforms on democracy. He is a member of two sub-committees of the Government of Karnataka drafting a new Agriculture policy of the state, He is an adjunct professor at NLSIU teaching Democracy and Ecology and is the state head of Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network. In the past, he has been the Executive Director of Greenpeace, the Global G20 campaign coordinator at ActionAid International and the Director of APSA – The Association for Promoting Social Action.

Ms. Vishala Padmanabhan, Social Entrepreneur and Consultant- Organic Food Systems

Ms. Vishala is a social entrepreneur who established the Buffalo Back Collective, inspired by the Gandhian idea of Grama Swarajya. She is also a Consultant in Organic Food Systems. She had been an early adopter of social entrepreneurship with intent to apply her acquired knowledge and skills to enable social, economic and environmental justice in food and agriculture systems. She also has 8 years of professional experience in international taxation and ITS audits and 12 years of experience in the wide spectrum of the Organic food landscape starting from Agriculture, development organisations to food enterprises. Specialised in Information Systems audits, she uses design thinking to problem solving in the development sector.

[This report has been prepared by Ashwin Lobo and Shrestha Chowdhury, Research Associates, ESG with inputs from Malvika, Satvika and Sneha]

An ambitious and overstretched objective of the webinar that wish to discuss and debate everything under the ‘climate change’ with no background papers.