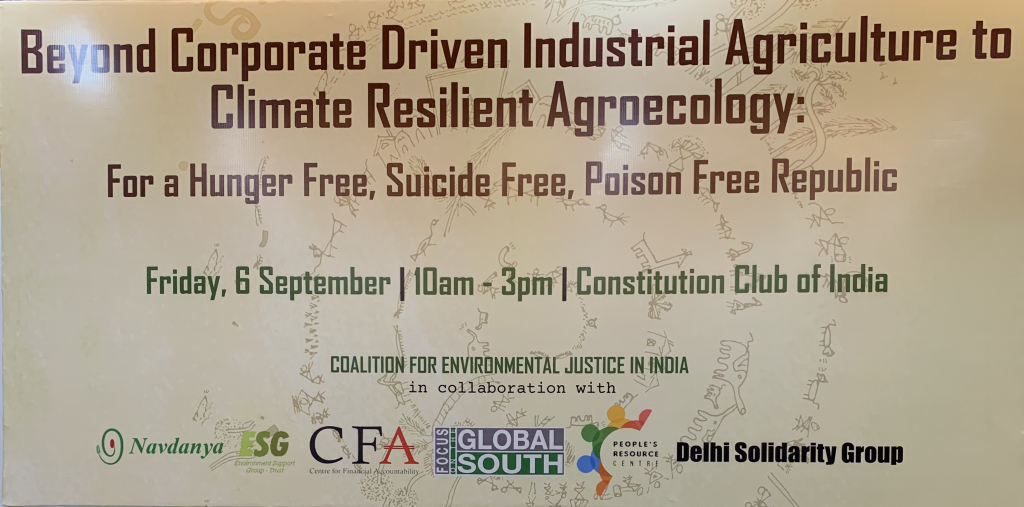

“Beyond Corporate Driven Industrial Agriculture to Climate Resilient Agroecology: For a Hunger Free, Suicide Free, Poison Free Republic” – Delhi Workshop Report

A clear and strong case was made to promote agroecology to save farmers and advance food security across India by speakers and participants at the workshop organised by Navdanya, Environment Support Group, Center for Financial Accountability, Delhi Solidarity Group, People’s Resource Center and Focus on the Global South, in collaboration with Coalition for Environmental Justice in India, on 6th September 2019 at the Constitution Club, New Delhi.

Welcoming the audience, Anil Tharayath of Delhi Forum introduced the purpose of the workshop as an effort at exposing aggressive capitalisation and commodification of farming which would weaken efforts in securing the interests of farmers and consumers. This trend, he said, has been particularly energised by policies of the current administration which is incentivising extractive development, in the process widening inequity and exacerbating environmental degradation.

It is in this context that various groups and networks have initiated conversations on securing environmental and social justice and engaging efforts to challenge prevailing anti-farmer policies by advancing agroecology as the choice of farming that works for present and future generations. Towards this end, Coalition for Environmental Justice in India has helped bring these conversations to different audiences nation-wide which is otherwise unnoticed by mainstream politics and media.

Bablu Ganguly from Timbaktu Collective, Anantpur (Andhra Pradesh) spoke about his experiences as a practising organic farmer working with a large network of farmers and farm focussed groups for about 40 years. He spoke of how in arid conditions where the predominant farming is rainfed, sustaining the health of the soil is critical for farming to succeed. The reality across India, however, is that soils have been extensively abused and quite are heavily degraded. Low organic matter and low soil moisture in soils is contributing to crop losses: crops start to wilt even when there is a 10 day delay in the onset of monsoons. To complicate matters, good quality and resilient seeds are rarely available to farmers. All this has resulted in reducing rural economies to tatters. The necessary symbiotic relationship between livestock and the farm, forests and agriculture, is almost non existent nation-wide.

Bablu addressed how young people today aren’t getting into agriculture. “It is not that children of farmers do want to get into agriculture because they are not interested. It is essentially because they do not know anything about farming,” Bablu warned. “The current education system does not include agriculture (as a major subject of study) and this has alienated children from agriculture. This has resulted in a loss of information, skills

The current situation of agriculture in India is grim and reminds him of the colonial period, when there were famines, and of the 50s and 60s, when the threat of a famine was employed to force India to import and depend on P. L. 480, which eventually resulted in the so-called ‘Green Revolution’. Overall, this has impacted the quality and resilience of Indian agriculture.

In this context, Bablu enquired about the nation-wide promotion of Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF). Having used the technique, promoted by Padmashri Subash Palekar (who has now renamed it as Subhash Palekar Natural Farming -SPNF), Bablu enquired how the universal introduction of this one method is a wise approach to address the crisis in Indian farming. Application of cow urine based concoctions, like jeevamrutha, into soil that is depleted of organic matter, is dangerous, Bablu said. “Initially, there will be good results as soil microbes start eating minerals in the soil (in the absence of soil carbon). But the fungi which do the real work of decomposition in soil need organic matter. Since organic matter is missing, and ZBNF advocates against introduction of fresh organic matter, microbial activity will eventually recede and productivity of crops could reduce”, Bablu warned.

What worries Bablu is that a one size fits all system is again being propagated nation-wide, and especially when it is not a method that works for the complexity of India’s farming: very diverse soil types, complex weather systems, varied agronomic practices, etc. The way in which ZBNF/SPNF is defined and being propagated is not even keeping with principles of agroecology, he highlighted. Yet, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation and United Nations Environment Programme has been uncritically promoting ZBNF as a major solution globally. Bablu expressed his deep worry over such formulaic interventions and hoped the workshop would strengthen efforts to highlight the urgency demanded in shifting to agroecology, in which ZBNF could be one technique adopted on a case sensitive basis.

Vandana Shiva of Navdanya took the audience on a journey of the roots of Zero Budgeting. Weaving a richly textured and historical narrative of India’s farming, she explained how when Sir Albert Howard was sent to India by the British in 1905 to improve agriculture, he was amazed by the richness of farming and termed Indian farmers ‘professors of farming for the world to emulate’. In a century since, India’s farming, she said, has been taken over by the “Poison Cartel”, a group of companies which control agri-chemical businesses globally and promote products that enriches them, but destroys people and the planet. Given the widespread prevalence of crisis in Indian farming, she wondered about the wisdom of promoting ‘zero budget farming’ as a viable option, when in fact farming need all the budgetary and other supports that can be extended.

Shiva questioned the attack on organic farming which to her is the accumulation of knowledge of living systems and employing its potential to promote humanity and protect nature. In that remained wise choices to come out of the crises of farming. But introduction of ideas like ‘Zero Budget’ in agriculture and the promotion of an artificial conflict between “natural” and “organic” is making room for agro-chemical companies to ensure their prevailing systems of raking profits continue. In this context she said “This is totally another divide and rule policy [that] has nothing to do with science or farming”.

Dr. Vandana Shiva delved deep into spelling out what constitutes Zero Budgeting. For her, it is basically a budgeting system in which every expense is squared off in ways that maximises profits for the investor. On the context of Indian agriculture it would mean cutting costs on services that support farmers – the most critical feature that run and sustain the agri-systems. Global investors are pushed for introduction of Zero Budget in agriculture because they have seen in it an entry point for them into the country’s agriculture business. Without the word “natural” Zero Budget Farming (ZBF), which has found endorsement in Government of India’s 2019 budget, can open doors to not just chemical farming in a big way, but also Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), artificial intelligence, genomic mapping of seeds, and surveillance technologies managing the country’s agriculture.

If ZBF is about limiting spending on external inputs then the country has already had such models of farming for centuries and are known by various names like organic farming, biodynamic agriculture, permaculture, Jaivik Prakritik and so on. So the agricultural model ZBF is proposing is nothing new. What it really is promoting is a corporate budgeting system for agriculture that is about privatising profits and socialising costs, and externalising costs (especially losses) to nature, the farmers and the consumers. Therefore the need of our time is not ZBF but a true cost accounting system that takes into consideration all costs to nature, to society and to health. In this context, Shiva also pointed out several misleading and misdirecting nomenclatures have come to dominate the domain of agriculture. One of them is yield per acre which measures neither the quality of the food produced nor the nutrition in the food nor the cost of farming. On the other hand are indices like health per acre that measures nutrition per acre and wealth per acre where the externalities are calculated and also allows farmers to have their own seeds, their own methods of farming, and have control over markets, which remain unheard of in conventional farming statistics.

At this critical juncture, therefore, agro-ecology emerges as the alternative which can protect the farmers’ sovereign rights over seeds, promote chemical-free mixed farming, increase farm productivity and output, promote climate resilient crops, and tackle rising rates of suicides among farmers. However, before this can happen, conditions need to be created in the country where farmers are able to make a choice for agro-ecology. Shiva argued that this is where the consumers can step in a major way to provide a fillip to the agro-ecology movement in Indian agriculture.

Leo Saldanha explained how he came to write his critique of Climate Resilient Zero Budget Natural Farming (CRZBNF) propagated since 2016 in Andhra Pradesh. He said he was piqued by the uncritical promotion of CRZBNF by UNEP in its June 2018 press release. Deeper enquiries revealed a slew of international organizations and financial institutions like the World Wildlife Fund, World Agroforestry Centre, BNP Paribas, and several other bodies of the UN promoted the programme, facilitated by Sustainable India Finance Facility. About US $ 2.3 billion(Rs 17,000 crores) was committed by this consortium to promote ZBNF. In addition, Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives (APPI) had granted a sum of Rs 100 Cr to the State of Andhra Pradesh (AP), which would be utilized to fund the Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (

To Leo, the programme was replete with contradictions. With the grant amount, RySS has hired “trainers”, mainly fresh graduates, to meet with farmers across the state and train them on the techniques of ZBNF. Farmers were conflicted as they were asked to move away from traditional and natural agriculture a few decades ago, and are now being trained back to adopt natural farming. What is worrying though, Saldanha said, is that the trainers have been asked to shadow, observe and document the farmers from close quarters all through the day and night and for a month at least. And this without any concern about how invasive this is and the serious ethical and moral questions arising from such an exercise. Despite several requests to share the agreements and documentation about the programme, APPI, RySS or the State of AP have not responded positively.

The second major contradiction in the aggressive promotion of ZBNF in AP is that it is advanced by a parastatal, RySS, and not as constitutionally required through the Panchayat Raj institutions, and through the District Planning Committees as mandated in Article 243ZD of the Constitution. Any major transition in farming clearly calls for ground up planning, directly engaging the farmers. But CRZBNF was being promoted in a highly centralised manner, with no documented evidence of involvement of Legislators and Panchayats in shaping the programme. Besides, farmers clearly were at the end of the system of planning, and essentially involved through Farmer Producer Organisations in implementing the programme.

The APPI grant was not limited to RySS but also included supporting a slew of several civil society organizations in AP to work in creating favourable conditions for the implementation to the programme. In addition, grants have been extended to various international research agencies, which were gathering extensive information on AP farming, information that was being sent out of India without any prior and informed consent from the farmers and farmers organisations.

The overall effort of the programme appears to be one of commodifying and financialising natural farming, Leo said, and evidence by reading out extracts from a letter written by Erik Solheim in August 2018, when he was Executive Director of UNEP, to Chandrababu Naidu, former Chief Minister of AP. In this letter, Solheim says: ““it is widely recognised that public funding will not be enough to tackle some of the most defining challenges our planet is facing: produce more food, stimulate economic growth and jobs, and reduce deforestation and tackle climate change”. Naidu had responded to this call by stating in a special conference organised on CRZBNF in New York by UNEP, on the sidelines of the 73rd UN General Assembly, as follows: “You can know the history of the food; which land it has come (from); what are the ingredients; what are the soil properties; that is the biggest advantage. I have a dash board to measure (performance of CRZBNF) against SDG achievements. Everything will be online. And there will be no corruption”. Naidu, Leo explained, had travelled to New York in search of collaboration to seek “finance, philanthropy, market sharing”, so that ZBNF could be taken “on a fast track to a global community”.

The programme relied on Farmer Producing Organizations (FPO), another parastatal, in building a grassroots network essential to promote the programme – aimed at converting all of Andhra Pradesh’s 8 million (80 lakhs) farmers to ZBNF. FPOs were also to assist in aggregating locally produced goods, not for local consumption, it appears, but potentially European Markets, Leo argued. This questions the basis of promoting ZBNF as a “climate-resilient” programme what with the heavy carbon footprint of transporting its produce globally. Besides, the sidestepping of Panchayat Raj bodies is unconstitutional, Leo explained, expressing his worry that this might further contribute to the fast dwindling importance of Panchayats. This when over the past three decades there have been various efforts to forestage Panchayat Raj system as the key decision making body and delivery mechanism relating to farming. This marked yet another feature of CRZBNF

He argues that a true climate-resilient model will be achieved only when Article 274ZD is implemented. The speaker also threw light on the secrecy surrounding the financial agreements of ZBNF as it is protected under Section 8 of thee RTI act which explicitly protects information related to National security and defense. The MoU, however, was released after being amended.

The adoption of this model by the NITI Aayog to implement it on a national scale without sufficient

Aruna Rodrigues, Lead Petitioner in India’s Supreme Court for a moratorium on GMOs, began her talk by asserting that GMOs have failed in India, as proven by data sets from the past 14 years. She maintained throughout her talk that GMO cannot coexist with agroecology for one reason, there will be contamination. “You either have agroecology or GMO, you cannot have both,” she said.

A study shows that insects are disappearing at an alarming rate. “They found that over 40% of our insect species are threatened with extinction and the rate of decline is 2.5% a year of the total mass of insects” which suggests that within 100 years, we may have no insects! The drivers for this extinction of insects are industrial agriculture, synthetic pesticides and fertilizers and other biological factors including climate change.

The second study shows that industrial agriculture contributes to Green House Gases (GHGs) and thus questions the rationality of the claim of corporate agricultural businesses that large scale industrial farming is necessary to “feed the world”. “Which is not true, of course” asserted Aruna. And continued to say, “GMO has a number of health problems. BT gene is toxic to the human gut system. With contamination, seeds get contaminated at the molecular level, so any toxicity will be irreversible”.

Aruna also spoke about two lessons from history “which can guide us now”, she said . In the first one, when the US wheat crops were hit by rust, a wheat type from Iraq was brought in, which was surprisingly resistant to four types of rust, 35 races of common bunt and so on. This saved US wheat crop. Uncontaminated gene pool “is a genetic treasure”, she said, arguing for global efforts to safeguard genetic diversity from GMO contamination.

The second example is of DDT, which was considered to be safe for decades and was extensively promoted globally. However, Barbara Cohn (from University of California, Berkeley) found that there was a link between DDT and breast cancer in women. Women who were exposed to DDT before the age of 14 were five times more likely to develop breast cancer than women who were not. Aruna drew parallels between the DDT study and how GMOs are being pushed now. This is a lesson for us now, as releasing GMOs today will unleash damage that cannot be undone “as it will cause contamination at the molecular level which is irreversible and irrevocable”, she warned.

In conclusion, Aruna argued that GMOs have failed and it is not practical to choose GMOs over agroecology as agroecology has proof that it will out yield GMOs and deliver traits of disease/ pest and

Vishala Padmanabhan, a chartered accountant turned organic farmer and safe food activist, by choice, and who runs Buffalo Back, spoke of her experience farming in a rain shadow area which has been drought affected for over 5 years. It is also a place where degradation from mining is rampant, which contributes to degrading the condition of farmers so much that even Below Poverty Line farmers would appear better off. And such are the conditions of most marginal farmers, and this too is worsening, she said. And if there is a method to bring them out of such abysmal poverty, the answer lies in empowering them to adopt community based farming guided by principles of agro-ecology, she argued.

Vishala said, “In terms of structural changes or innovations we don’t see anything better than community based organisations at present…where we are trying to strengthen the Panchayats to take up governance of community based organisations [so that] they become little prototypes of changes which will holistically take care of every principle under agro-ecology concept”. While it is important to concentrate on mobilising farmers to take up agro-ecology, Vishala also stressed on the pressing need to come out with strategies to educate the market about what agro-ecology offers and how it is different from the branded organic produce that are widely available today. Using Wendell Berry’s quote, “Eating is an agricultural act”, she said that it has become crucial to propagate Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) in which anybody who consumes participates in the food production system.

Therefore, PGS is not just about farmers. It stands for bringing all stakeholders on one platform of the agricultural system. In India, especially, such an exercise is important because the organic movement in the country was not triggered by consumers, who for the longest time have had access to safe food. However, in the last couple of years things have changed and the consequence of which has been a tremendous growth in domestic consumption of organic food. At this juncture of time, the principles of agro-ecology need to reach the consumers through stories—stories based on facts that talk of resilience of farmers who have efficiently battled the massive Kerala floods or those who are flourishing in dry and arid regions like Leh and Ananthpur, or the real practices that translate into actual nutritious products.

Vishala also spoke on how ZBNF is a practice or a tool while agro-ecology is a comprehensive approach that accommodates not just practices that produce the tangibles from soil, water and the seed, but also the intangibles such as economic viability, social justice and fair pricing.

Vishala’s also focused on generating more dialogue on such matters, and not just about making technology more usable and markets more accessible to farmers. It is also critical, she argued, that the process of data accumulation on farming which is underway, is regulated, which today it is not, and held the Central Government accountable for this serious lapse.

Prof. Dinesh Abrol of Institute for Studies in Industrial Development began his intervention by drawing attention to a paper written by Ashlesha Khadse and Peter Rosette about how ZBNF is taking agroecology to scale. While such efforts are interesting and need to be regarded, Abrol said he comprehensively resonates with Leo Saldanha’s critique of Andhra Pradesh CRZBNF, which he argued is a tool of recolonization and also empowers right-wing authoritarian approach to farming. Agroecology, he said, is not just about farmland, but about ecological landscapes. It is critical to understand that agroecology contributes to soil fertility, biodiversity, and water availability, as much as it does to empowerment. “These elements are not being engaged with at all in the Subhash Palekar Natural farming”, Dinesh highlighted. He expressed worry that the kind of framework of farming that has evolved in Andhra Pradesh could make way for contract farming, and then corporate farming.

Dinesh Abrol also maintained that the method of CRZBNF is no different from how ‘Green revolution’ and ‘GMO Revolution’ have been pushed. He argued that irrational promotion of ZBNF without understanding its implications, to society and ecosystems, is authoritarian in nature. “This is because it excludes a certain set of people from farming choices and includes only allies. This lack of inclusiveness will ensure that the landless labour will suffer while the rich farmers control agriculture”, explained Abrol. He also stressed on the importance of understanding how agroecology stands for inclusiveness, rebuilding rural ecosystems, thus improving alliances between labour and farmers.

It is very important to demystify the whole thing and “for this opening the black box of promotion of ZBNF is a must”, he argued. He called for activists to engage with this particular debate, mobilize a discourse and advance fair and transparent practices of formulation of policy on farming and food security. He concluded by saying that we must do everything to oppose ZBNF, as it is now promoted, which he held is an effort to recolonize farming, especially in how right wing authoritarianism is employing the system in promoting its divisive project.

P. Sainath, editor of People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), gave a colourful talk on the prevailing situation of farming and natural resource dependent communities in India. He explained about privatization of knowledge has translated into the private control of almost all material resources. One of the biggest agendas of NITI Aayog currently is the privatization of water. The implications of this can be seen across towns in India, which now have private water, that is provided through ‘pilot projects’. These ‘pilot projects’, which is a corporitized name given to privatization of water, claim it is about greater efficiency in water distribution. But what this is essentially, is transfer of water resources from the poor to the rich, which only increases inequalities, and further desensitises the rich.

Sainath said “we cannot and should not look at the market as an independent, spiritual and sentimental entity. Rather, we have to critically look at who controls the various resources, who has the decision making power in the country and who influences or controls consumers to make decisions”. He gave the example of the USA where 75% of organic food, the consumption of which is a right choice, is controlled by corporates and they now have the power to decide what the meaning of ‘organic’ is. Similar situations can arise when the Finance Minister decides to not include the ‘N’ for natural, in ZBNF.

Sainath then spoke about PARI’s current efforts with UNDP doing a series on climate change, understanding the impact of climate change, through the documentation of the lived experiences of ordinary Indians. The series has, as of now, covered the lives of fisherfolk in Tamil Nadu, hailstorms and floods in Maharashtra, the Yak economy in Arunachal Pradesh and more. Sainath said that the term ‘climate change’ itself is a corporatized and compromised term. It is a replacement for ‘global warming’ that has more weight and brevity of the damage that the Earth is currently experiencing and is more discomfiting than the term ‘climate change’. Sainath then narrated three interesting stories that captured the essence of the experiences of ordinary people due to climate change.

His first story was on the status of fisherfolk in Pamban, Tamil Nadu. He said that fisherfolk are entering deeper into the sea, on their kattamarams, due to the lack of availability of fish near the shores. This is because of the warming of the water and the exploitation of the waters through the unsustainable extraction of fish by trawlers. This has resulted in several deaths of the fisherfolk as their kattamarams are not equipped to traverse so far into the sea. Another story Sainath narrated is about a woman belonging to the fisherfolk community who said that the fish that they used to get in 1993, they now only see on Discovery Channel. “Although this is a humorous account, it is an account of despair and says a lot about the loss of biodiversity and livelihood as a result of climate change”. Sainath also spoke about how the Yak economy in the Himalayan regions is on the verge of collapse, as climate change affects pastoral nomadic communities. The Yak, which is a hardy animal in extreme cold climates, finds it difficult to be productive in even slightly warmers climates. This along with the changes in land, use as a result of pasture land being captured by the elites, doubly affects the pastoral communities, who are being destroyed.

Sainath’s talk was followed by a Question & Answer session with the audience. The discussions that followed were on the nature of the conversations that surround ZBNF, on climate change and the water ciris. in response, panellists broadly made a case for a shift to agroecology as a sure way to minimise the risks of adverse impacts. For which there is a critical need to make it a political cause, they argued.

Madhuresh Kumar of Peoples Resource Centre spoke about how the agrarian distress in the country is not being acknowledged, the scale and intensity of it is not reported, and the Government is now manipulating, even blocking, release of data on the extent and rate of farmer suicides. Given the extractivist paradigm of promoted by the current administration, it appears certain that agrarian crisis will only worsen, unless there is a comprehensive change in governenance.

Ranjini Basu of Focus on the Global South spoke about how the agrarian distress is an outcome of unimaginative and contradictory policies promoted by the Government. To tackle agrarian issue, it is essential to take into account income disparities, asset ownership, gender, caste and other inequalities that plague the Indian agricultural system. However, none of these are being factored in, and instead uncritically ZBNF is being promoted as a solution to tackle such fundamental inequalities.

About the livestock economy, which happens to be the focus of ZBNF, Basu said that it is extremely resource intensive. Yet, to claim the method as zero budget, especially when it is livestock centric, is gross misdirection, she argued. When indegenous livestock population in India has dropped by 9% in the past few years, cattle ownership is sparse and the nature of ownership is riddled with inequalities, it is quite difficult to imagine how ZBNF would build equity amongst farming communities. To focus on the livestock issue, the Government started Rashtriya Gokul Mission for the conservation of native breeds. However, Ranjini said, this project is so narrow and myopic in its focus, that it does not take into account the cost of livestock, and instead focuses only on protecting the genetic purity of the cattle. This Government project, when situated in the context of various layers of inequalities that exist in the agrarian society, results in further discrimination of the landless and the poor. This disincentivises farmers from keeping cattle.

Another issue that Ranjini spoke about was the costs that farmers get for their produce. The claim of the government is that ZBNF would reduce input costs. However, the input prices are high and the minimum support price has not been rising with the rising cost of production. This, coupled with the opening of the Indian agricultural market to the international market, an increase in contract farming and unregulated markets, has put a stress on production in the country. Without a proper pricing policy, promoting ZBNF could be disastrous to farmers, Ranjini warned. She concluded her talk with a short note on the impact of the agricultural crisis on women. When women do not have formal land titles and access to inputs, it comprehensively disallows them to compete with male counterparts. Therefore, any approach that is taken to solve the agricultural crisis should look at all aspects of the cultivation and post cultivation processes, and the social conditions of farming communities.

Vijoo Krishnan of All India Kisan Sabha highlighted how disparities in Indian farm sector is simply not a concern for the ruling classes. “Extensive evidence of child malnutrition do not shock the country as much as the Sensex dropping a couple of points”, he said. “When we are talking about the issues of agriculture, it is important to talk about the bad politics and policies that encourage the corporatization of agriculture”, Vijoo argued. “These policies are a result of the neoliberal paradigm that followed the 1991 reforms. This is also largely responsible for the accentuation of the agrarian crisis”, he asserted. There is an urgent need for uniting various forces to tackle the Adani and Modi promoted exploitative model of development and bring in an alternative paradigm through which an alternative politics can also be created, he said.

The workshop concluded with Leo Saldanha thanking everyone for their active participation.

Report prepared by Leo F. Saldanha, Sahana Subramanian, Abhijna Bellur and Sana Huque.

Video recording of the workshop is by Media Collective, Delhi.

Good post

The conference has thrown light on various issues concerning agrarian crisis and possible remedies thru technologies, change in the system and policy issues. I am of the firm opinion that ZBNF in its totality will certainly reduce cost of production, obtain crop yields on par with chemical agriculture after at least 3 years,, besides promoting healthy food for consumers. I am aware of radical elements commenting on any new thing is common. There is nothing wrong in promoting zbnf in about 10% area in the country by 2030. I am the professional writer for SDG goal 2 in karnataka, highlighted all these points in our report.