“Government May Appear Insensitive, But It Cannot Ignore Voices Coming From Different Parts Of The Country”: Jairam Ramesh

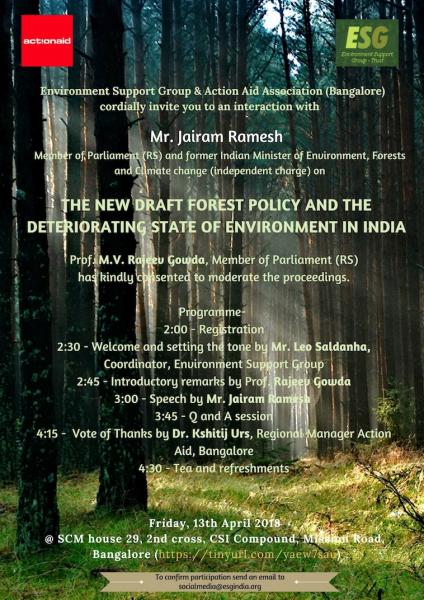

Report of the Interaction on “New Draft Forest Policy and Deteriorating State of Environment in India” organised by ESG and Action Aid

13 April 2018

“Government may appear insensitive, but it cannot ignore voices coming from different parts of the country”: Jairam Ramesh

Youtube link to a recording of the event: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLU4L5fiT4Ub9nfDlTKlVELF38Umg-GdoG

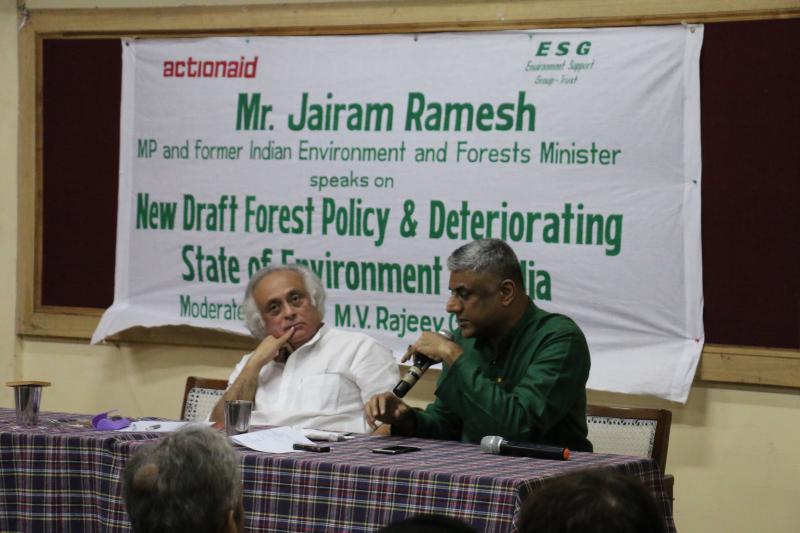

To a hall packed with people from various walks of life – academics, adivasis, students, journalists, trade unionists, administrators, etc., Mr. Jairam Ramesh, former Indian Environment Minister (2009-11) and currently Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) said: “the leasing out of degraded forest land to private industry opens up the door for privatising many of our forests in the name of improving the quality of our forests”. Mr. Ramesh was speaking at a town hall type meeting organised by Environment Support Group and Action Aid Association on the topic: “New Draft Forest Policy and Deteriorating State of Environment in India”. Prof. Rajeev Gowa, Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) coordinated this most engaging discussion that covered a range of topics: state of Ganges, risk to civil society today, air pollution monitoring, Western Ghats, weakening of environmental regulation, future of National Green Tribunal, etc.

administrators, etc., Mr. Jairam Ramesh, former Indian Environment Minister (2009-11) and currently Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) said: “the leasing out of degraded forest land to private industry opens up the door for privatising many of our forests in the name of improving the quality of our forests”. Mr. Ramesh was speaking at a town hall type meeting organised by Environment Support Group and Action Aid Association on the topic: “New Draft Forest Policy and Deteriorating State of Environment in India”. Prof. Rajeev Gowa, Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) coordinated this most engaging discussion that covered a range of topics: state of Ganges, risk to civil society today, air pollution monitoring, Western Ghats, weakening of environmental regulation, future of National Green Tribunal, etc.

In his welcoming remarks Mr. Leo Saldanha, Coordinator of Environment Support Group, said Mr. Jairam Ramesh is the only Environment Minister who has taken environmental issues out of Paryavaran Bhavan to where they belong, with the people. Saldanha shared how the public hearings that Ramesh held on whether India must allow GMO foods (B.t. Brinjal) for instance, drew thousands from all walks of life. It was a very complicated exercise as it involved listening to multiple voices and demands in seven locations across India. Ramesh had followed up with similar hearings on the Coastal Regulation Zone and the Green Mission. As Environment Minister and later as Rural Development Minister, Ramesh has addressed complex and contentious issues and tried to bring a politically difficult convergence. An example is the reform of the archaic Land Acquisition Act, 1894. Such a praxis of throwing open doors of a Central Ministry to people has set unprecedented standards of governance, which has not been emulated since.

Saldanha also drew attention to prevailing challenges where progressive environmental jurisprudence, which has been built over decades as an outcome of thousands of struggles and hundreds of judicial interventions resulting in historic legislations, is now being systematically dismantled, and that through executive actions. This is indicative in the Draft National Forest Policy 2018 which disregards the basic tenets of the historic Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA). The basis of such efforts is the TSR Subramanian Committee Report, which was Prime Minster Narendra Modi’s first major policy initiative on being elected. The basic proposition of this policy is to have “utmost good faith” in industry and business to “self-regulate” their environmental compliance, which, in effect, is to advance the dismantling of the prevailing environmental regulatory regime.

Saldanha also drew attention to prevailing challenges where progressive environmental jurisprudence, which has been built over decades as an outcome of thousands of struggles and hundreds of judicial interventions resulting in historic legislations, is now being systematically dismantled, and that through executive actions. This is indicative in the Draft National Forest Policy 2018 which disregards the basic tenets of the historic Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA). The basis of such efforts is the TSR Subramanian Committee Report, which was Prime Minster Narendra Modi’s first major policy initiative on being elected. The basic proposition of this policy is to have “utmost good faith” in industry and business to “self-regulate” their environmental compliance, which, in effect, is to advance the dismantling of the prevailing environmental regulatory regime.

Thereafter, Prof. Rajeev Gowda facilitated the discussion and invited Mr. Jairam Ramesh to make some introductory comments. Ramesh began by sharing his concern over the brutal Khatua incident and suggested that the non-adoption of the FRA in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, due to prevailing political climate, may have “tragically” contributed to the “horrific” tragedy of the Bakarwal community. Being evicted repeatedly from forests, despite being traditional forest dwellers, and thereby denying them their due rights to the forest, may have weakened their socio-economic status, he suggested. This results in political vulnerability, giving room for such horrific campaigns for their exclusion, and on communal lines. But even in states where FRA is being implemented, it is being resisted by forest departments. The “forest bureaucracy is dead against FRA”, asserted Ramesh. But, “we cannot evict people in this country. We cannot do what the Chinese do”, Ramesh said.

The division in India’s environmental community over FRA is contributing to non-implementation of this law, which was enacted with the specific purpose of correcting historical injustices committed against adivasis and other forest dwelling communities, Mr. Ramesh said. This situation is allowing governments to say “there is no consensus, so we will override the provisions of the Forest Rights Act”. As a result, only 14 lakhs families (of the 35 lakhs claims made) have got forest rights, and the FRA has been very poorly implemented in recognising community forest rights.

The division in India’s environmental community over FRA is contributing to non-implementation of this law, which was enacted with the specific purpose of correcting historical injustices committed against adivasis and other forest dwelling communities, Mr. Ramesh said. This situation is allowing governments to say “there is no consensus, so we will override the provisions of the Forest Rights Act”. As a result, only 14 lakhs families (of the 35 lakhs claims made) have got forest rights, and the FRA has been very poorly implemented in recognising community forest rights.

Another key reason for this resistance to implement FRA is the territorial mentality of Forest Departments, Mr. Jairam Ramesh said. He cited how the Gram Sabha of Menda Lekha in Orissa, for instance, earned only Rs. 12 lakhs a year from bamboo before the implemention of community forest rights. But after the rights were secured, the Gram Sabha’s income rose to a phenomenal Rs. 1 crore, and such revenue streams Forest departments don’t like to let go off. But Ramesh also echoed concern that some forest dwelling communities have become highly “individual centric” and governments are worried they may use the power gained from rights settled to promote mining and infrastructure developments within forest areas. But that does not mean State Governments can be trusted either, he suggested. The prevailing two-stage forest clearance procedure must remain for when decisions “come to Delhi”, since it is removed “from the pressure point”, some good forest cover has been saved.

Ramesh agreed with a submission that “one of the great tragedies in Indian ecology is the progressive loss of grasslands”. While this is because of the unprecedented spread of agriculture and irrigation in recent decades, it is mainly because “grasslands are considered as waste lands” and there is “…a problem with the waste land definition”. Ramesh stressed that “(t)he concept of wasteland is a dangerous one”, explaining that “for a forester, grasslands is not in a scale of priority”. The forest departments are mainly concerned with “good density forests” and thus have contributed to “a severe loss of grasslands”.

Focusing on the prevailing paradigm of development, Mr. Jairam Ramesh highlighted that “environmental regulation is seen to be a speed breaker in the ease of doing business”. The prevailing emphasis on “growth, investment, (increasing) GDP and (in advancing) the ease of doing business … environment is a casualty”. And it is “not a casualty in terms of rhetoric (alone), but in actual action” which is evident particularly when the “government favours one corporate group over another”. He cited the example of Tadoba Tiger Reserve where a massive coal mine by Adani Group is being promoted overlooking all statutory norms and protective measures.

seen to be a speed breaker in the ease of doing business”. The prevailing emphasis on “growth, investment, (increasing) GDP and (in advancing) the ease of doing business … environment is a casualty”. And it is “not a casualty in terms of rhetoric (alone), but in actual action” which is evident particularly when the “government favours one corporate group over another”. He cited the example of Tadoba Tiger Reserve where a massive coal mine by Adani Group is being promoted overlooking all statutory norms and protective measures.

The systematic weakening of environmental regulation in India is particularly worrying, and the result is “pollution continues unabated”, Ramesh said. Yet the government is not addressing the issue, and wakes up to it only when there is a major crisis, as was the case with Delhi last year. While “air pollution has become more political than ever” the “same concern is not present for water pollution”, he pointed out. Perhaps this is because “it is not there in our consciousness”. This is not to suggest air pollution is not a serious problem, for a recent study by an Indian scholar from University of Toronto suggests that between 2000-2015, air pollution is the cause of 8% of all death in India. All this suggests a need for critical and substantive response from the Government, and Ramesh said the current government is taking some positive steps, and an example is the push to achieve all vehicular transport fuels achieve the best emission standards by 2020.

On the prevailing state of affairs of the National Green Tribunal (NGT), Mr. Jairam Ramesh explained he had gone to the Supreme Court of India and secured a stay against the current Central administration’s employment of the Finance Bill to “emasculate” the forum and thus “took away all (its) powers”. Ramesh asserted that NGT “did more than any other (judicial body) to make environment truly a peoples’ concern”. The forum was set up to ensure easy access to environmental justice, and is an unprecedented judicial reform globally, he said. He called for keeping up the pressure to ensure “NGT continue to be the way it was originally structured under the 2010 Act”.

On the prevailing state of affairs of the National Green Tribunal (NGT), Mr. Jairam Ramesh explained he had gone to the Supreme Court of India and secured a stay against the current Central administration’s employment of the Finance Bill to “emasculate” the forum and thus “took away all (its) powers”. Ramesh asserted that NGT “did more than any other (judicial body) to make environment truly a peoples’ concern”. The forum was set up to ensure easy access to environmental justice, and is an unprecedented judicial reform globally, he said. He called for keeping up the pressure to ensure “NGT continue to be the way it was originally structured under the 2010 Act”.

Prof. Rajeev Gowda enquired how one could deal with some of NGT’s decisions, such as the one demanding no development zone of 75 metres around all lakes in Bangalore, which is quite unimplementable. Ramesh agreed all of NGT’s decisions aren’t sound and “to say that there is no conflict between the goals of protecting the environment and meeting goals for providing security of tenur or livelihood” it live in “fool’s paradise”. And continued to suggest that “very often these objectives de not converge with one another”, and highlighted that “it is the job of the political process, the political executive and the local governments to resolve the issues”. But, “the answer is not to disband the NGT”, Ramesh asserted. He gave the example of the development of the Comprehensive Environmental Pollution Index (CEPI) that identified 88 industrial clusters as critically polluted, which also are densely populated clusters, and such situations offer significant challenges.

The discussion continued to touch on various issues and concerns that were raised by the audience. Mr. Ramesh concluded the proceedings on the note that civil society must stay united and raise difficult questions. “It is possible to democratise environmental decision making” even as “we create jobs for the 10 million Indians who come into the labour force every year”. For this, the “political leadership must have the courage to promote economic growth with ecological balance”, Ramesh suggested. But a serious threat to such democratic processes is in the propensity of current Central administration to outsource formulation of key laws and policies to “think tanks”, in place of debates and discussions in “civil society which had an institutional forum” and “civil society was heard” under the Congress regimes. He admitted that Congress too has had its share of attacking civil society, as was the case with alleging S. P. Udaykumar and hundreds of others were “anti-national” merely for opposing the Kudankulam nuclear project. But the difference is that the current Central administration has “closed its doors on civil society” forcing many civil society organisations to close down. He exhorted civil society institutions must organise and fight back this trend, for “governments may appear to be insensitive, but they cannot affort to ignore the voices emerging from different parts of the country”.

The discussion continued to touch on various issues and concerns that were raised by the audience. Mr. Ramesh concluded the proceedings on the note that civil society must stay united and raise difficult questions. “It is possible to democratise environmental decision making” even as “we create jobs for the 10 million Indians who come into the labour force every year”. For this, the “political leadership must have the courage to promote economic growth with ecological balance”, Ramesh suggested. But a serious threat to such democratic processes is in the propensity of current Central administration to outsource formulation of key laws and policies to “think tanks”, in place of debates and discussions in “civil society which had an institutional forum” and “civil society was heard” under the Congress regimes. He admitted that Congress too has had its share of attacking civil society, as was the case with alleging S. P. Udaykumar and hundreds of others were “anti-national” merely for opposing the Kudankulam nuclear project. But the difference is that the current Central administration has “closed its doors on civil society” forcing many civil society organisations to close down. He exhorted civil society institutions must organise and fight back this trend, for “governments may appear to be insensitive, but they cannot affort to ignore the voices emerging from different parts of the country”.

Dr. Kshitij Urs, Regional Manage of Action Aid Association, a co-host of the interaction, brought the proceedings to a close by thanking Mr. Jairam Ramesh and Prof. Rajeev Gowda. He thanked Mr. Ramesh for being candid and willing to interact without reacting to any problematic questions, a characteristic that has become rather rare amongst politicians today. Urs thanked Prof. Gowda for facilitating this town hall type gathering and being a bridge to civil society from within the Congress party, as head of its research wing. The audience was thanked for their enthusiastic and informed participation.

close by thanking Mr. Jairam Ramesh and Prof. Rajeev Gowda. He thanked Mr. Ramesh for being candid and willing to interact without reacting to any problematic questions, a characteristic that has become rather rare amongst politicians today. Urs thanked Prof. Gowda for facilitating this town hall type gathering and being a bridge to civil society from within the Congress party, as head of its research wing. The audience was thanked for their enthusiastic and informed participation.

Report prepared by ESG Team

community outreach,campaigns,biodiversity,brinjal,hasiru usiru,forest policy,jairam ramesh,Prof. Rajeev Gowda,State of Environment