Reclaim & Turn Inclusive, Bengaluru and its Blue-Green Common: Workshop Report

Report of the workshop organised by ESG

on 4th February, 2023

(Video recording of this event can be accessed here)

(Download the pdf version of this report here)

Introduction

Leo Saldanha, Coordinator and Trustee of ESG, opened the session by recalling his time growing up in Bengaluru when the city used to be a melting pot of cultures. He describes it as a place where people of different ages, caste, religion and gender would live together in relative harmony, where there were open discussions in public places, where access to commons didn’t depend on wealth and where everyone could use and play in parks and open spaces freely. That Bengaluru does not exist anymore, and its deeply worrying that the current younger generations cannot experience such freedoms. He also noted how financialisation of land has had a direct impact on extent and quality of open spaces, and the territorialization of these commons has reduced access substantially. This has also translated into serious loss of biodiversity across the city, he said, and shares how the number and diversity of migratory birds has dropped drastically in a matter of two decades. Besides, public health – especially of children, of those from poor and working classes particularly – is being severely compromised due to persisting neglect of our blue-green commons. He highlighted the critical importance of multiple publics coming together to reclaim commons to ensure the metropolis could guarantee a reasonably good quality of life for all.

Bhargavi Rao, Senior Fellow and Trustee of ESG, shared various efforts in preserving such commons. Organising protests in almost every road proposed for widening, against alignment of metro going through parks and open spaces, climbing trees to prevent their felling, against privatisation of lakes, organising workshops and seminars to sensitise key decision makers, promoting mobility and accessibility to all – not only those with cars, are all efforts that succeeded in retaining what greenery and open space we still see. Speaking on ESG’s long and ongoing struggle to gather inter-sectoral support for protecting, conserving and rejuvenating lakes in Bengaluru, she highlighted how this resulted in a framework for deep democratic efforts, as with the direction of the Karnataka High Court for formation of lake protection committees.

Accessibility and Functionality of Blue-Green Commons

In 2005 and then again in 2008, ESG, along with Hasiru Usiru, challenged the road widening scheme which promoted unnecessary and indiscriminate felling of trees on an equally questionable and preposterous claim that it would reduce traffic congestion. A variety of interim directions were issued directing the State, planning and municipal agencies to ensure public involvement in decision making is made normative. Despite such judicial scrutiny when reckless expansion of roads and tree felling continued, the Court took suo motu cognizance and instituted a PIL in 2011. The outcome was a direction that required the BBMP to set up Greening Committees, an order that remains without compliance till date.

Even as recently as 2018, a PIL was filed for the implementation of the Karnataka Preservation of Trees Act 1976 (Tree Act). The outcome of all these cases were several directions ordering strict compliance with the Tree Act, adoption of re-greening strategies, constitution of a Tree Authority, replanting of cut trees, constitution of a Tree Court, etc. Despite the legal framework, our blue-green open spaces continue to be threatened by various infrastructure and development projects – almost always without any public scrutiny.

Vijay Narnapathi, Architect, spoke of how the increase in Bangalore’s density would not be so bad if public transport was accessible and public commons much bigger and more accessible than now. From his view, the prevailing laws and judicial orders had substantially slowed down road widening, as tree lines worked to protect pedestrian pathways. In some areas, footpaths have actually become wider – which he argued is a major win due to public action. Trees are crucial to improve walkability, he said.

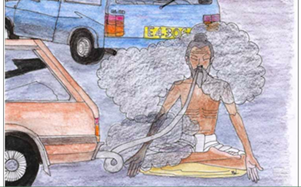

Suprabha Seshan of Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary, recalled her accidental experiment during the COVID lockdown of 2020 – she took to walking comprehensively everywhere, a process that continued for about 68 days, covering about 750 kilometres. This journey allowed her the time and space to build a deep connection with biodiversity of the city. Unfortunately, she said, we have lost the joy of walking in the city – which is a deeply empowering activity. What we now have is akin to living in a gas chamber, and emphasised that there aren’t any technocratic solutions out of this mess: walking and cycling will remain pollution-free methods of commuting, and can save the metropolis.

Shaheen Shasa ofBengaluru Bus Prayanikara Vedike emphasised that reducing congestion should be of highest priority since it is what leads to destruction of the commons. She suggested the best solution is spreading use of public transport. She added that the percentage of people in the city using buses has reduced from 40 % to 30%, mainly due to lack of support for BMTC from the Government. She lamented that with a population of 1.3 crore has an equal number of private vehicles but only 6000 buses – 5000 new private vehicles are added daily. She wondered how long we will be told that the metro rail is a solution to congestion, when it really is not. She recalled such debates and discussions have been a part of the Hasiru Usiru, ESG and other processes over the past decade and more, and wished there was willingness on the part of the political and administrative establishment to listen.

Disparities in urban Development and Disruption in Bengaluru’s Potential to be an Inclusive Metropolis

The Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. (BMRCL) has been subjected to grave criticisms due to the lack of planning, disruption caused to other modes of transport by the way it is designed and constructed, unnecessary felling of trees, destruction of landmark locations and the sheer amount of time that it has taken to build the project. More recently, the metro pillar accident that cost the life of a mother and child highlights serious risks latent to this project which aren’t addressed. In 2009 ESG filed a PIL challenging the southern reach of the metro on various technical and planning grounds, and also the utter lack of public involvement. Despite specific directions mandating strict compliance with the KTCP Act, the Metro continues to be built in extremely damaging ways.

Dr. Usha Rao, an independent urban researcher, brought up this reality of the Metro and highlighted how the project is eating into commons. She also raised concerns over the absolute lack of spaces of protest and even congregation of the public, and that developmental plans were sanitising the city of its natural politics and culture. Recalling acquisition of three playgrounds near Bamboo Bazaar for metro lines, she pointed out that this was not only outside the scope of the project, but directly targeted spaces critical to low-income communities and minorities. Parks and open spaces in privileged layouts, in contrast, were protected by the same agency. She called upon all groups to come together to protest against such divisive planning and infrastructure creation and to once more reclaim streets like the publicly motivated 2008 protests that brought about substantive positive action from the civic and state governments.

Priya Chetty Rajagopal of Heritage Bekupointed out the lack of integration with intermodal transport networks, as is evident in constructing the Cantonment metro station – which is 900 m away from a railway station, is indicative of the callous disregard for mobility and accessibility. When multiple protests took place to draw attention to this anomaly, the official response was in creating divides and instilling fear amongst people. There is so much value in ensuring our open and blue-green spaces remain healthy and accessible, she added, recalling how during the pandemic lockdowns, Bangalore’s parks came to life, with wildlife reclaiming them. Key to sustaining biodiversity rich healthy open space, Priya said, is in ensuring the public have a role in shaping the outcomes. Reality though is that citizens of Bangalore have become its biggest tourists and forgotten about the heritage they possess within knocking distance of their homes.

Ebenezer Premkumar of All Saints Church Congregation narrated how the incredible All Saints Church and its garden would have turned into a metro station, were it not for the systematic and carefully considered efforts of the congregation with ESG. He especially acknowledged the support received from Leo Saldanha, Priya Chetty Rajagopal, Meera Iyer (Intach), Gautam Krishnan and others who were there through the struggle and gave much needed confidence to the congregation to stand up and fight to save the church even when the Church leadership was keen on selling it off. It took over 4 years, involved conciliation efforts from the European Investment Bank (a key project financier), and also some pathbreaking willingness to correct the damage by Anjum Pervez, IAS, who now heads BMRCL, that today not only has the church been saved from structural damage, but it biodiversity rich garden too has survived for posterity – 133 trees were saved and only 7 trees were removed. This, Premkumar pointed out, is what the power of the people can achieve.

Sathya Prakash Varanashi, an architect and heritage conservationist, spoke on how heritage spaces in Bangalore are being lost progressively. While heritage buildings are privately-owned, their heritage value is a public good. The lack of efforts to reconcile this schism, has resulted in the loss of multiple heritage buildings and spaces. Urbanisation is a causal factor for this divide between public good and private interest, but there are ways to resolve this and ensure we can escape the historical trap of private interest compromising that of the public. This problem we see in the city is felt across the country, as territorialisation of commons, lack of support from the State and extractive intent are displacing communities and their relationships with heritage and the commons.

Building on this stream of conversation, Krishna, a resident of Malleshwaram, pointed to how public grounds are privatised by designated portions of it to multiple private uses: such as badminton club, volleyball club, etc. The playground on Malleshwaram 5th Cross, which was once an open space used by the locals for sports and community activities, is now highly regimented and gates and fences have restricted access to the general public. Other public places have also faced a similar fate, like the Beagles Basketball stadium which has turned from a public space to a private coaching centre. Almost every park in Bangalore has high metal fences and brick walls on the periphery restricting access, in contrast to parks in other cities where no such restrictions exist. He expressed concern on the lack of activism from the general public against such issues.

Planning from the Ground Up

Cubbon park has been described as “A welcoming buffer zone under an open, liberal sky, a capacious green sink with an ability to subsume not only carbon dioxide but also a diversity of ideas and opinions, the Park has always been a space that carries in itself the very DNA of the city that Kempagowda built.” in ‘Cubbon Park: The Green Heart of Bengaluru by Roopa Pai[1]. Yet, the park has been a constant target by the government over years for illegal diversions such as park denotification, LH Annexe construction, restriction on park access, constructing 7- storey building, proposal of a smart city, and more. Constant public vigilance is the way forward in securing critical spaces.

On that note, Gautam Krishnan, a member of We Love Cubbon Park, pointed out how the Rs. 40-crore smart city project in Cubbon Park was more about destroying the park. This money could easily have been invested in so many other parks which need support. All that Cubbon Park really needs is some gentle maintenance. Speaking of how the Smart City project got into the park, he shared how a namesake consultation was conducted by project authorities, without notice to push what they already had designed and decided, offering no scope for any public input. In effect, the process ignored the very people who regularly use the park, and also those who visit it frequently. The process of planning was ad hoc, haphazard, with contractors calling the shots based on budgetary considerations and not from improving the park. He concluded saying that the city’s character has fundamentally changed with massive expansion of its population, and perhaps there is now a renewed need to build grassroot level processes to collate peoples views and imaginaries.

Mahesh Bhat, who has been working to conserve the Hesaraghatta catchment area, talked about how authorities with their narrow and inadequate understanding of the implication os developments they propose, guided by considerations of commercialization, decide on making roads, layouts, bridges, etc., resulting in the perpetuation of injustices and existing inequalities. Development should encompass a wide range of factors, including economic, social, cultural, and environmental dimensions, and should prioritise the well-being and advancement of all members of society, he argued. It is important to critically engage with the term and idea of development, contest it so a more holistic and inclusive kind of progression could result.

Tara Krishnaswamy, co-founder of Citizens for Bengaluru said that there is doom and gloom in the state, but there are also bright spots and citizens need to build on them and take charge in a democracy. The idea of creating and maintaining public spaces was a matter for pride for past establishments, a tradition that began with the Mughals and continued through to the Mysore Maharaja’s time. However, today, the state tends to be guided by budgets and not shared visions of creating healthy, charming cities. Privatisation of governance has also led to private individuals profiting from public lands, and developers who are not local, and who do not have any interest in maintaining the spirit of the city, have come to define the nature of land, space and form. To change which, she suggested, citizens must form collectives in every ward, raise funds, buy scraps of public land, and employ the best architects to design newer public spaces. She emphasised the importance of proactive action instead of merely protesting to reject what the state and civic bodies propose. She reiterated the need to lead by example of positive action and start thinking out of the box.

Arathi Manay from Citizen Matters stressed upon the importance of local citizens’ participation in managing common spaces, as opposed to corporations or authorities. Using an example of Puttenahalli lake in South Bangalore, she explained that it has been maintained by local residents who have contributed funds (around Rs. 8-12 lakhs annually) to protect the lake as a nice open space. At Citizen Matters the focus is on hyperlocal issues and encouraging citizens to be pro-active. Sharing some examples of successful action, such as painting speed breakers, promoting the “2 bin 1 bag” campaign, and advocating for better waste management practices are showcased, she called for a persistent engagement ground up.

Quality and Quantum of Blue-Green Commons for a Healthy, Inclusive and Biodiversity Rich Bengaluru

It isn’t sufficient that our blue-green commons are merely accessible to the public, but it is absolutely necessary that they are healthy, inclusive and biodiversity rich. The city is a very different place now than it was a quarter century ago due to the rapid urbanisation. The frenetic pace of development is honed on valuing every square foot of land in financial terms. Serious effort to ensure the approx. 1200 sq. kms. of built up space of the metropolis is healthy, secure, safe and an accessible habitat to over 15 million people (1.5 crores) is sorely missing. An alarming indicator is in a 2022 study done by Jayadeva Institute of Cardiology of 5000 patients, all below 40: 30% had developed cardiovascular diseases without any past family history, which is unprecedented.

Conservationist Prem Koshy highlighted the importance of retaining the charm of the city as a method to make space for biodiversity and wildlife. Transformation of natural spaces into concrete structures in the city is decimating urban wildlife, and this could have major health consequences. He explained how snakes play a crucial role in maintaining the ecosystem as they consume diseased animals and prevent the spread of disease. If the ecological balance is healthy, the wildlife will prosper and they will provide us much needed public health. “No snakes, means more rats, less seeds, more pests, no pollination and no plants.”

Joseph Hoover of United Conservation Front pointed to the impact of urban expansion threatening wildlife and reducing bird diversities, as in Rajarajeshwari Nagar. While he called for consistent public action to resist destruction of natural spaces, he expressed deep worries over how the government continues to commercialise forests. “We need to support each other and come together to fight against unscrupulous leaders who only think about capitalising on our forests. Unless we stand together, we will have lost. It’s up to us to come, talk, and fight together in this difficult battle” he remarked.

Battles (Lost & Won) to Reclaim Bengaluru’s Blue-Green Commons

Srinivas of the Dalit Sangharsha Samithi shared how the residents of Mavallipura came together to protest and reclaim the village and its commons from being a landfill site. This successful battle, he said, had not only forced Bangalore to transform its waste management strategies, forcing segregation at source, but also shut down the Mandur landfill. Besides, it resulted in the transformation of the country’s laws on waste management, a core feature of which is to protect commons. Unfortunately, he lamented, despite Court orders, there is weak implementation. He emphasised the importance of changing lifestyles to effectively preserve nature. “If we keep going on like this, the forests will be destroyed, the lakes will be destroyed and nature will be destroyed. We must come together as we are from nature, and nature is from us” he says.

Ramesh, from Ramagondanahalli village shared his experience on how the city’s relentless expansion is destroying agropastoral regions, watersheds and biodiversity, as is the case now with 17 villages impacted by Dr. Shivaram Karanth Layout, a mega project proposed by the Bangalore Development Authority. The entire project is without proper social, economical or environmental impact assessment. Despite the doors of justice being shut on them repeatedly, the communities are determined to not allow their fundamental right to housing, livelihood and a clean environment to be destroyed. Speaking to the denial of their right to protest, Ramesh said there is need for people everywhere to rise up and question the legitimacy of a High Court ruling that requires anyone in the Bangalore rural and urban districts to only protest within the confines of the old Jail, now ironically Freedom Park.

The right to protest is intrinsic to a deeply democratic society and ensconced in the fundamental right of expression. Not only do we have the right to protest but we also have the right to protest in any common public space. However, in August 2022, the Karnataka High Court effectively banned protests from being held anywhere in the city except Freedom Park, on the ground that they obstruct traffic. Thus, effectively curbing our right to protest.

Vinay Sreenivasa from Alternative Law Forum highlighted how the streets provide a space for the voices of a democracy. As the lifeline of a democracy, the public has a right to access the streets and use them to make their voices heard. However, the Karnataka High Court and State Government have taken serious steps to infringe and restrict people’s right to protest on the street commons, pointing to the ban on protests anywhere but Freedom Park. He spoke about the plight of farmers from Devanahalli (50 kms from Bangalore), who took to the streets to protest the acquisition of their farm lands for an Aeronautical park, but an FIR has been filed against them citing the High Court order. Protests are organised to convey people’s demands to the authorities for appropriate action and this cannot be done by restricting it to a park far away from the affected area. Vinay called for substantive action by civil society to protest the order and restore people’s fundamental rights.

Ways Forward to Reclaim Bengaluru’s Blue-Green Commons and its Democratic Polity

The final session involved an interaction between Brijesh Kumar, Ravichander V, and Prof. Rajeev Gowda. The major thrust was on efforts required to reclaim Bengaluru’s blue-green commons and its democratic polity.

Brijesh Kumar, IFS, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Legal) at the Karnataka Forest Department, spoke of challenges balancing rapid development and protecting commons. Bengaluru has been centred around advancing private interests, he said, resulting in commercialization of land. This is posing problems in advancing life sustaining aspects of a city. He expressed concern over the subordination of a key regulatory functionary, the Tree Officer of Bangalore, within the BBMP – thus s/he is forced to approve tree felling applications from the Commissioner which is against the maxim of law that one cannot be a judge in one’s own cause. Recalling an High Court order where it was said permission for felling trees is given in the evening and trees are cut overnight, he feared this subordination might be the reason. He compared Bengaluru to a chicken that has grown to the size of a goat but still has the same size capillaries; referring to narrow roads that can’t handle the increasing traffic. He believed Metro could be a solution in the very long-term solution, from an environmental perspective, but for the present the prevailing congestion and resultant damage to commons is a serious concern.

Ravichander V, Chairman of the Bangalore International Centre, and who also worked as member of the BBMP reorganisation committee pointed to a crucial need to define ‘commons’ in ways that could ensure their protection. Pointing out how most infrastructure projects were promoted without due diligence, he said the system has perfected the art of extracting commons under the guise of infrastructure projects, ultimately benefiting a select few at the cost of everyone else. A demand for accountability is imperative in bringing about change in such a state of affairs, as the bureaucracy is ridden with apathy. While GIS Maps would help define commons – accurately define the contours of the commons, with the buffer zones and other safeguards – the lack of its active employment in day to day decision making is allowing for their encroachment and misuse. The system is inherently opaque and turning it transparent is arduous, but a battle worth fighting for. In which digital access to all plans will go a long way, but this needs to be buttressed by a serious effort to decentralise administration and devolve power to local government. Terming the Constitutional 74th Amendment (Nagarpalika) Act, 1992 as a half-hearted measure, and the lack of focus on building local governments from inception of the country a criminal neglect of the Constitutional promise, he argued for an energetic effort to move in that direction to rescue the metropolis from its prevailing chaos.

Prof. Rajeev Gowda, former MP (Rajya Sabha), spoke of how the system has tried to bring about change where possible and some success has been achieved. Post the recent floods, the government has been more proactive in its actions and the system is much more aware that something has to be done. However, effective implementation and effectuation of solutions is lacking, and the difficulty lay with the State’s capacity and attitude. The state is now focussed on wealth accumulation and has deviated from its welfare objectives. He asserted that now is the time to declare spaces sacrosanct and bring in a preservation mindset. The positive aesthetic association to preservation and the alarm caused by floods makes it a good opportunity to intervene, he suggested.

Asha Kilaru of the Bangalore Birthing Network and CIVIC Bangalore spoke of the need to consider access to commons from a perspective of maintaining public health. This determinant can evolve public spaces that are inclusive and accessible. For instance, why is there no importance attached to massive expanses of public spaces in hospitals and other institutions, guaranteeing public access to them, she wondered. She recalled how the fervour of the 1990s when there was so much proactive engagement with reclaiming the city and its commons is clearly missing today, and public action is largely constituted of reactive responses. There is a need to qualitatively transform citizen engagement with civic power to ensure there is movement towards sustainability, Asha remarked.

In that context, Usha Rao spoke to the hands-off approach in regard to Metro, over projecting its benefits and thus disallowing other options of mobility. Ravichander V responded that those involved in promoting the Metro were simply unaware of the consequences of their actions, and quite simply dindn’t care to think far enough. When the metro needs to be planned with the horizon of a century and more, in Bangalore it has become a reaction to dealing with congestion without appreciating the importance of nesting it organically into the metropolitan growth.

Sathya Prakash Varanashi added that the development of a city comes from the cumulative effort of four stakeholders, namely – Experts, Administrators, Politicians and the people. Experts know how to draft plans but don’t have the power to implement them. Administrators don’t have the expertise to draft plans and Politicians had different agendas apart from development of the city. The people only know what they need but they lack the power or the expertise to take things forward. Therefore, even if one has to consider it to be an utopian context, bringing these four parties must be the path on which the city needs to walk.

Leo Saldanha concluded the session by recalling the injustices created by restricting the right to protest, which created an undemocratic city. Besides, the widening disparity in access to public spaces, based on one’s economic status, and the continuing lack of importance given to these spaces, he argued, is seriously impacting quality of life in Bangalore. Such conversations as were being held, he said, are critical to identifying the pathways to transformations and for challenging imposed undemocratic authority.

Names and Affiliations of Speakers

Vijay Narnapathi, Architect

Suprabha Seshan, Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary

Shaheen Shasa, Bengaluru Bus Prayanikara Vedike

Dr. Usha Rao, Independent Urban Researcher

Priya Chetty Rajagopal, Heritage Beku

Ebenezer Premkumar, All Saints Church Congregation

Sathya Prakash Varanashi, Architect and Heritage Conservationist

Gautam Krishnan, We Love Cubbon Park

Mahesh Bhat

Tara Krishnaswamy, Citizens for Bengaluru

Arathi Many,Citizen Matters

Prem Koshy, Conservationist

Joseph Hoover, United Conservation Front

Srinivas, Dalit Sangharsha Samithi

Ramesh,Dalit Sangharsha Samithi

Vinay Sreenivasa, Alternative Law Forum

Brijesh Kumar, IFS, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Legal) at the Karnataka Forest Department

Ravichander V, Bangalore International Centre

Prof. Rajeev Gowda, former MP (Rajya Sabha)

Asha Kilaru, The Bangalore Birthing Network and CIVIC Bangalore

[This report has been prepared by Nidhi Hanji, Sachin P S (advocates associated with ESG) and Amrita Menon (an ecologist associated with ESG) with inputs from Akshita Raghaw, Mridul Tripathi, Pardhasaradhi Tirumalasetti and Vivek Shrivastava (Interns at ESG).]

[1] Roopa Pai (2022) Cubbon Park: The Green Heart of Bengaluru, Speaking Tiger