Two Waste Management Stories From The Dakshina Kannada District

By: Janani S, The author is an architect and researcher on inclusive urbanism at Environment Support Group.

Pachnady was still over 2 kilometres away but the stench of garbage reached us early. In 2019, the Pachnady landfill was in the news due to its slide down during the monsoons engulfing the residences and a temple in the vicinity. The solid waste of the city has polluted the groundwater here beyond repair rendering it unfit for drinking. Many of the farmers and other victims await their full compensation even after two years and their livelihoods witness a standstill as they are unable to cultivate in these degraded lands. In this context, we, researchers from the Environment Support Group, visited the waste management facility of Pachanady, Mangalore to get a better understanding of the prevailing situation.

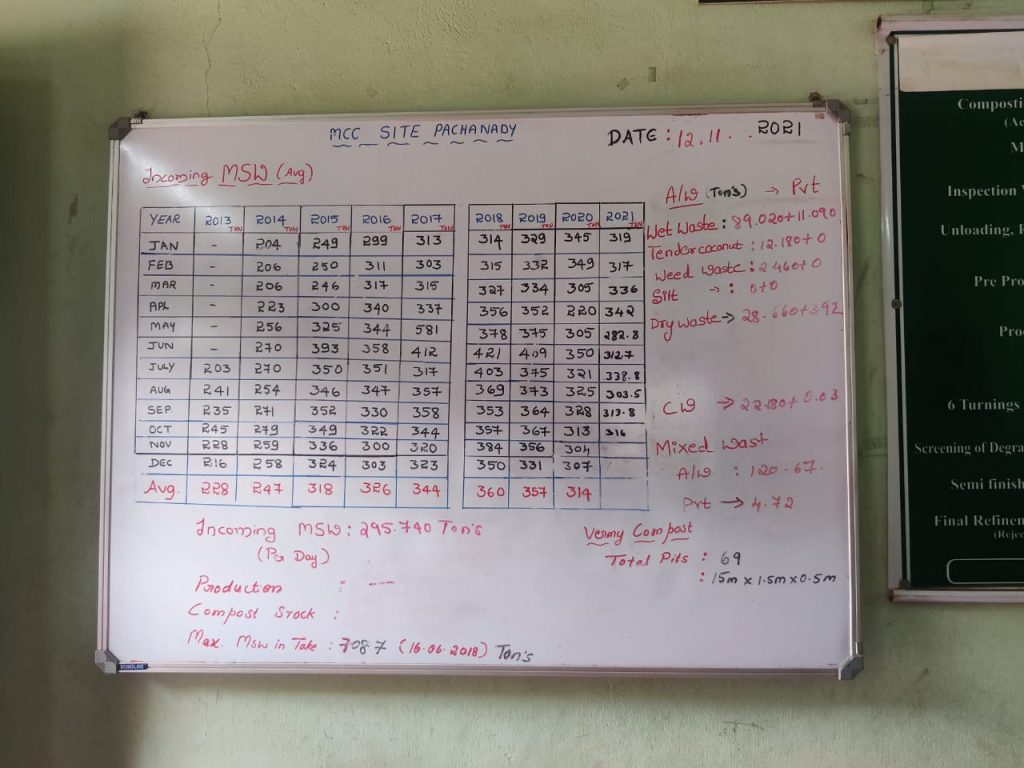

Pachanady waste management site data board indicating the quantity of Municipal Waste from 2013 to 2021; PC: Sana Huque

The site supervisor at the facility, Mr. Benny was a resourceful person who walked us through the various processes involved in management of the municipal wet and dry waste at the facility. An average of 300 tons of municipal solid waste, mainly from Mangalore, is managed here everyday. He told us that the municipality collected wet waste 6 days a week and dry waste once a week.

One of our first observations was that the workers here worked without any protective equipment, such as masks or gloves and were subjected to extremely unhygienic conditions. The workers may have become immune to the repulsive odours but certainly not to the respiratory disorders that are a consequence of the hazardous working conditions.

Pre processing zone: Windrows turners at Wet waste management site, Pachanady; PC: Vani Sharma, Sana Huque

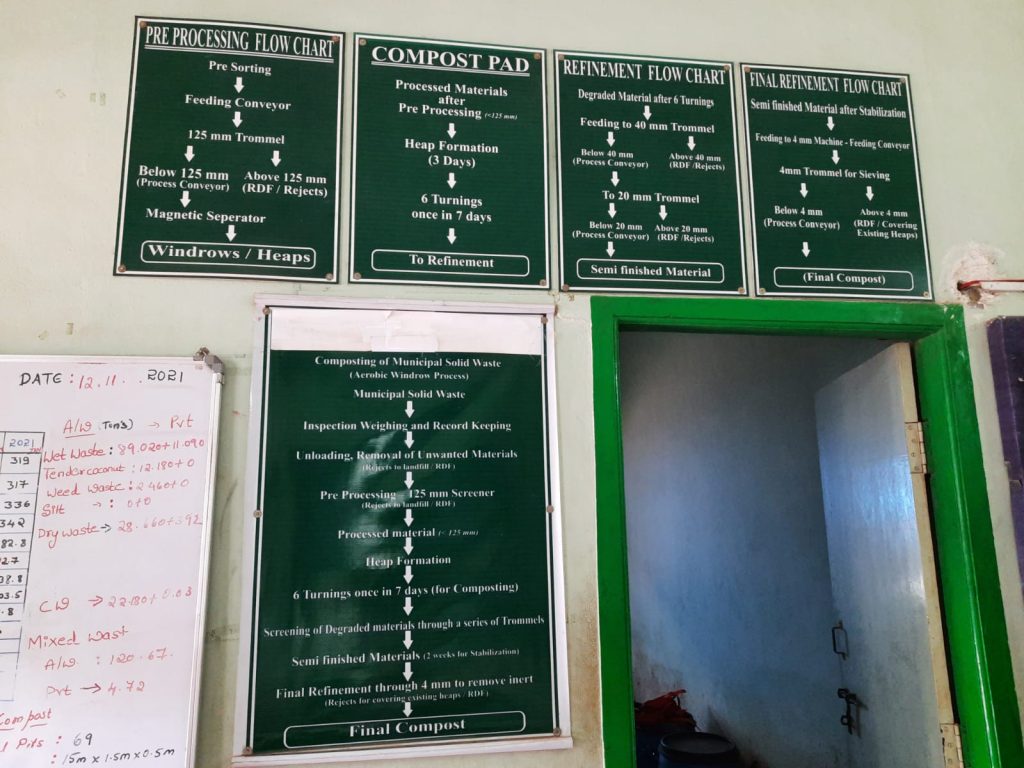

The wet waste management facility was demarcated into three zones. First was a pre-processing unit where heaps after heaps of the city’s wet waste was collected. Large mechanised compost turners were used to turn the wet waste allowing aeration. This method of composting was aerobic in nature and called the windrows system.

The second zone was a composting platform where black soldier flies Hermetia illucens (BSF), a species of decomposer flies larvae, were introduced into rows of low-height wet waste piles. This zone in the facility was contracted out to a private agency. After a period of 14 days, when the BSF has helped break the organic matter down to a partially decomposed state, the BSF are removed out of the waste and given away to the fish feeding industry which benefits from the larvae’s high protein content. The entire process of breeding the BSF from egg to larvae is carried out off site by the private agency.

Composting pad using larvae of black soldier flies at wet waste management site, Pachandy; PC: Vani Sharma

We reached the final zone which is the sieving area consisting of 40mm, 20mm and 4mm sieving trommels. Here, partially decomposed waste runs on a conveyor system into a series of sieve trommels to be collected as fine fertile compost, which is sold by the Municipality to farmers. In the process of wet waste processing, a lot of nutrient-rich black liquid called leachate is released. Leachate can be extremely hazardous when it penetrates the ground and mixes with groundwater, and is the major cause of death and diseases in landfill affected communities. An elaborate leachate collection and processing plant has been set up within this facility to ensure safe leachate treatment.

L: Sieving trommels and conveyor belt system ; R: Leachate treatment plant, Pachanady site; PC: Vani Sharma

Even after the arduous, energy-intensive, 15-day long process of converting wet waste to useful compost in the facility, at least 20 percent of wet waste ends up as rejected and is sent to the nearby landfill. This is because of non-segregation at source and a resultant plastic content in the wet waste which cannot be separated out.

Thereafter, we walked down to the dry waste processing unit. Plastic formed the largest chunk of the dry waste including PET bottles and single use plastic covers. These are segregated and then compressed by machinery to form compact plastic bales. Such bales, weighing upto 700kg each, are sent to a cement industry for use as fuel, a process in which, the burning of the consolidated plastic bales, releases toxic and carcinogenic gases. When we process plastic in such a manner, we are only shifting the toxins, that would have otherwise entered the soil or water systems, into the air. It is certainly not a comprehensive solution as it pollutes the air severely and leads to respiratory diseases.

L,C: Plastic bales ready to be sent to the cement industry for use as fuel, Pachanady site; R: Construction of concrete drain at the Pachnady landfill to collect the leachate PC: Sana Huque

Our visit, just like the rejected waste, culminated at the Pachnady landfill. Nestled between beautiful green surroundings, the waste piles stood tall and the soil in the entire zone was embedded with layers of plastic. There was a massive concrete drain being constructed at the edge of the site, clearly an attempt to divert and contain the toxic leachate. Mr. Benny told us that there was a plan to collect the leachate and transport it to the waste processing facility for its treatment. It was a frightening insight into how the measures taken were insufficient and ambiguous while they continue to damage our ecosystem.

In a workshop conducted by Environment Support Group in collaboration with Mangalore city Council on Solid Waste Management on the 13th November 2021, the Commissioner of Mangaluru stated that there is no other patch of land that can be earmarked for a landfill due to the hilly terrain of the city and non availability of sparsely populated flat land. With these practical limitations, one wonders what can be a better solution to the looming waste crisis. Fortunately, the answers are not very far away.

In nearby Ullal city, a lot of headway has been made on the processing of wet waste locally at the ward level. In the ward Kallapu, in the modest surroundings of a farmland, we visited one such facility for managing wet waste. Here, Mykro Greens Enviro Solutions, a startup formed by three young Engineers, is working along with the Ullal City Council to create a decentralised model of aerobic wet waste composting at ward level. The system devised is zero energy, using no electricity at all, and most importantly does not release any leachate into the ground.

Decentralised wet waste processing unit in Kallapu, Ullal L: Safwan, co founder of Mykro Green explaining the process to ESG team; R: 600 sft sheltered space processes 500kg waste per day in zero energy technology

They employ a simple windrow system of 4 low-height piles with layers of waste and microbial coco peat. The coco peat helps absorb the leachate and also provides the necessary aeration for composting. Over a period of 16 weeks, with the weekly turning of the wet waste to maintain aeration and right temperature, the decomposition is completed. The mixture is then sieved to obtain the final compost, sold locally to the farmers. The total space required for the management of wet waste of 500kg, servicing about 500 houses in the ward, was 600 square feet of sheltered area.

Sometimes solutions to vast problems can be modestly simplistic. Decentralised system of waste management is a highly efficient and low-energy system which requires no external electrical energy, no need for large flat patches of land, humongous equipment, large treatment plants or landfills. It is truly decentralisation at ward and area sabha levels that can be the solution for the waste problem especially in times of climate change.